Importance Of Urine Albumin-Creatinine Ratio In The Diagnosis And Prognosis Of Chronic Kidney Disease

The significant role played by albumin-creatinine ratio in chronic kidney disease has long been acknowledged by the scientific community. For one, it helps determine its progression.

Author:Suleman ShahReviewer:Han JuJan 19, 20241.2K Shares100.8K Views

How important is the albumin-creatinine ratio in chronic kidney disease?

The New Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines represent a significant change from the National Kidney Foundation’s Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF KDOQI).

Based on the KDIGO guidelines, the urinary albumin/creatinine ratio is now integral to the classification of chronic kidney disease.

The urinary albumin-creatinine ratio (uACR)has been found to be fundamentally important for both the diagnosis and the prognosis of chronic kidney disease (CKD).

It is now recommended that all patients with diabetesor hypertension be screened annually with this test.

The presence of albuminuria helps decide the medications for the treatment of hypertension.

This review discusses the importance of urine albumin-creatinine ratio in chronic kidney disease.

Discussion

Worldwide, the incidence of chronic kidney disease is on the rise, and it generally remains asymptomatic until advanced stage.

Only 10% of chronic kidney disease patients are recognized by primary care clinicians.

A study conducted in 2011 found that approximately 39% of U.S. citizens with end-stage renal disease had never consulted a nephrologist prior to initiation of dialysis.

Kidney disease is very costly in the Medicare population.

Major risk factors for chronic kidney disease are:

- diabetes

- hypertension

- age (60 years or greater)

- a family historyof chronic kidney disease

Current populations detected with chronic kidney disease may be significantly under-represented because proteinuria/albuminuria test is underutilized.

In the U.S., the lifetime risk estimate of chronic kidney disease surpasses that of other common conditions, including:

- coronary disease

- diabetes

- invasive cancer

Importantly, chronic kidney disease is a major cardiovascular risk, which is equivalent to that of either having diabetes before a heart attack incidence.

The level of kidney function predicts:

- the risk of myocardial infarction

- mortality rate

The aim of this review was to discuss the importance of urinary albumin-creatinine ratio in the diagnosis and prognosis of chronic kidney disease.

Diagnosis And Staging Of CKD

The most significant change in the new KDIGO guidelines (versus the original KDOQI guidelines) is the new classification that makes the urinary albumin-creatinine ratio as important as estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in evaluating the severity of the disease.

The recommendations call for characterizing chronic kidney disease based on underlying cause, GFR category and albuminuria category, as all these influence:

- clinical management

- outcomes

- mortality

A rapid increase in mortality happens once the eGFR drops below 60 ml/min/1.72 m and/or once the urinary albumin-creatinine ratio rises above 3.0 mg albumin/millimole (mmol) creatinine.

The effects of both eGFR and urinary albumin-creatinine ratio are additive in causing mortality in patients with both chronic kidney disease and acute kidney injury.

Opportunities to delay progression of the disease and prevent cardiovascular events are lost if the clinician relies only on changes in eGFR and serum creatinine to diagnose and follow the progression of disease.

Chronic kidney disease is diagnosed based on low eGFR, which is less than 60 ml/min/1.73 m, and/or urinary albumin-creatinine ratio of greater than 30 mg albumin/g creatinine.

The urinary albumin-creatinine is also known as the microalbumin test.

There must be two consecutive abnormal values for eGFR and/or urinary albumin-creatinine of at least 90 days apart to confirm the diagnosis of chronic kidney disease.

The eGFR is widely accepted as the best assessment mean of kidney function because:

- eGFR is usually reduced only following widespread structural damage

- most of other kidney functions decline in parallel with the GFR

As eGFR declines, patients experience:

- higher rates of drug toxicity

- acute kidney injury

- chronic kidney disease complications

- cardiovascular disease

- all-cause mortality

Direct measurement method of GFR is not routinely available to clinicians; therefore, estimated, or eGFR, is derived from serum creatinine and biometric variables of:

- age

- gender

- race

- serum creatinine

It is reported as part of a standard metabolic profile by most of the laboratories.

Currently the preferred formula is CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration), as it is more accurate for estimating GFR above 60 ml/min/1.73 m.

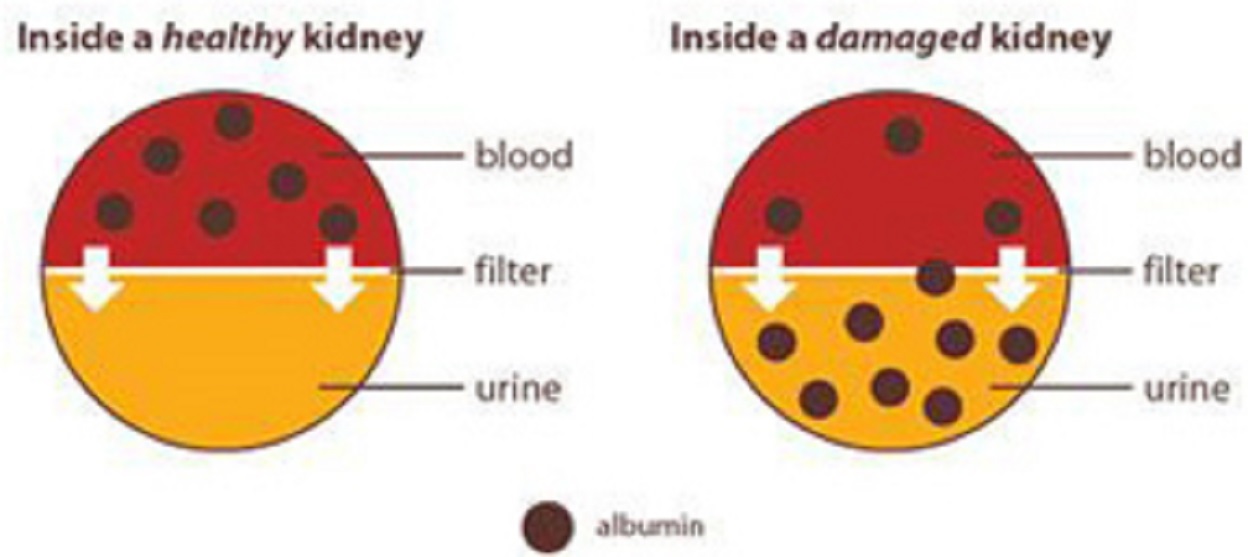

Albuminuria is currently the primary laboratory indicator for ongoing kidney structural damage, and is the principal urine protein in most of the renal diseases.

It is the earliest marker of glomerular disease and often appears before any reduction in eGFR.

Physiologically, albuminuria is related to endothelial damage and correlates with both cardiovascular disease and retinopathy.

Despite recent emphasis on the importance of assessing urine microalbumin levels regularly in diabetes patients, there is widespread inconsistent use and misapplication of the term in clinical settings to include everything, from dipstick assessment of total protein to the intended quantitative measurement of urinary albumin-creatinine.

Too low levels of “microalbuminuria,” which is referred to as urine albumin, are to be detected by a routine urine dipstick test.

KDIGO recommends discontinuing the use of microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria levels in favor of the terms“moderate” and “severe” albuminuria.

For each GFR stage, the degree of albuminuria is an independent risk modifier.

Recent studies have suggested that urinary albumin may play a causative role in renal damage.

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) blockade has been demonstrated to reduce albuminuria and reduce the rate of eGFR decline.

For simplicity and clinical relevance, current recommendations suggest recognition of three categories of albuminuria.

Stage A1: Urinary albumin-creatinine ratio less than 3 mg albumin/mmol creatinine level is currently considered to be physiologic level

Stage A2: Urinary albumin-creatinine ratio 3-29.9 mg albumin/mmol creatinine, formerly microalbuminuria, now referred to as moderate albuminuria

Stage 3: Urinary albumin-creatinine ratio equal or greater than 3 mg albumin/mmol creatinine, formerly macroalbuminuria, now referred to as moderate-to-severe albuminuria

Risk related to the level of albuminuria is continuous, that is, it is graded across the spectrum, and current categories may be revised, based on the results of ongoing studies.

Levels of 15-30 mg/ml (15-30 mg albumin/mmol creatinine) may prove to be clinically significant, as it has been demonstrated recently that even as little as 1.5 mg albumin/mmol creatinine is associated with an increased risk of adverse events.

Some researchers have referred to those with <3 mg albumin/mmol creatinine as normoalbuminuric (or similar terms) to distinguish these patients from those with undetectable urine albumin.

The Prevention of Renal and Vascular End-stage Disease (PREVEND), another recent population-based studies, have suggested that albuminuria of less than 3.0 mg/mmol is associated with increased risk factors for chronic kidney disease and mortality.

In addition, it is a potential early indicator of glomerular hyperperfusion and elevated GFR in the early stages of diabetic glomerulonephropathy.

Levels above 30 mg albumin/mmol creatinine are already recognized by specialty centers, such as levels more than 220 mg albumin/mmol creatinine in nephrotic syndrome.

Screening And Monitoring With UACR

Although a recently published article indicated a 60% lifetime risk of Stage 3 chronic kidney disease or worse in the U.S. population, which may foretell trends in other developed nations, routine screening of all adults is not recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

It is also unlikely to be cost-effective, according to the Belgian PREVEND study.

KDOQI and KDIGO guidelines recommend obtaining urine protein or albumin-creatinine ratio annually during the routine physical examination for adults, with risk factors for chronic kidney disease, including:

- hypertension

- diabetes

- family history of chronic kidney disease

- age greater than 60 years

The prevalence of chronic kidney disease increases with age, prompting the U.S. National Kidney Foundation to recommend screening of all adults aged 60 years and older, in response to a recent finding that 6 of 10 U.S. adults will develop chronic kidney disease.

Owing to the widespread availability of non-prescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in many countries, coupled with public unawareness of the potential renal risk, routine screening of older adults can help identify and monitor individuals at a higher risk.

Additional risk groups may benefit from routine checking of urine albumin-creatinine ratio, though the evidence supporting its efficacy is lacking.

Those with the following are also at a higher risk:

- impaired glucose tolerance/metabolic syndrome

- atherosclerosis

- a history of acute kidney injury

- certain autoimmune disorders

- smokers

In addition, recent evidence indicates that obesity is an independent risk factor for chronic kidney disease, even in the absence of other known predictors.

African-Americans tend to develop kidney disease 10-15 years earlier than the general population; therefore, earlier screening may be warranted for this group.

Management Of Albuminuria

Measurement of albuminuria is an indication for the treatment of hypertension with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor blocker.

Dual RAAS blockade with spironolactone has also been found to be helpful.

This, of course, comes with the caveat that potassium must be carefully monitored in such circumstances.

However, safety signals of acute kidney injury and hyperkalemia in the ongoing telmisartan alone and in Combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial (ONTARGET) and Nephron D trials suggest that dual RAAS blockade with an ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme) inhibitor and ARB (angiotensin receptor blocker) should be avoided.

Intensifying monotherapy with ACE inhibitors or ARB may be a better strategy.

Conclusion

Diagnosis and classification of chronic kidney disease require assessment of both eGFR and urinary albumin-creatinine ratio.

The urine albumin-creatinine screening should be incorporated into routine assessments for all at-risk adults.

This screening can be integrated into other chronic care processes.

This will enhance the ability of primary care providers to detect and manage kidney functional change, and to refer to the nephrologist when appropriate.

The most effective treatment is RAAS blockade and avoidance of NSAIDs.

More research is needed to know:

- if delay of progression of albuminuria results in improved clinical outcomes

- whether the rate of increase of albuminuria is a poor prognostic indicator

The albumin-creatinine ratio in chronic kidney disease is something worth exploring and studying.

Suleman Shah

Author

Suleman Shah is a researcher and freelance writer. As a researcher, he has worked with MNS University of Agriculture, Multan (Pakistan) and Texas A & M University (USA). He regularly writes science articles and blogs for science news website immersse.com and open access publishers OA Publishing London and Scientific Times. He loves to keep himself updated on scientific developments and convert these developments into everyday language to update the readers about the developments in the scientific era. His primary research focus is Plant sciences, and he contributed to this field by publishing his research in scientific journals and presenting his work at many Conferences.

Shah graduated from the University of Agriculture Faisalabad (Pakistan) and started his professional carrier with Jaffer Agro Services and later with the Agriculture Department of the Government of Pakistan. His research interest compelled and attracted him to proceed with his carrier in Plant sciences research. So, he started his Ph.D. in Soil Science at MNS University of Agriculture Multan (Pakistan). Later, he started working as a visiting scholar with Texas A&M University (USA).

Shah’s experience with big Open Excess publishers like Springers, Frontiers, MDPI, etc., testified to his belief in Open Access as a barrier-removing mechanism between researchers and the readers of their research. Shah believes that Open Access is revolutionizing the publication process and benefitting research in all fields.

Han Ju

Reviewer

Hello! I'm Han Ju, the heart behind World Wide Journals. My life is a unique tapestry woven from the threads of news, spirituality, and science, enriched by melodies from my guitar. Raised amidst tales of the ancient and the arcane, I developed a keen eye for the stories that truly matter. Through my work, I seek to bridge the seen with the unseen, marrying the rigor of science with the depth of spirituality.

Each article at World Wide Journals is a piece of this ongoing quest, blending analysis with personal reflection. Whether exploring quantum frontiers or strumming chords under the stars, my aim is to inspire and provoke thought, inviting you into a world where every discovery is a note in the grand symphony of existence.

Welcome aboard this journey of insight and exploration, where curiosity leads and music guides.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles