Inferior Infarct - Causes, Symptoms And Treatment

A coronary artery obstruction causes an inferior infarct or inferior wall myocardial infarction (MI), which results in reduced perfusion to that area of the heart. Patients with an inferior infarction exacerbated by a heart block, simultaneous precordial ST-segment depression, and RV involvement have bigger infarctions and a poorer prognosis than patients who do not have these symptoms.

Author:Suleman ShahReviewer:Han JuNov 14, 20229.5K Shares638.5K Views

A coronary artery obstruction causes an inferior infarctorinferior wall myocardial infarction (MI), which results in reduced perfusion to that area of the heart.

Unless treated promptly, this causes myocardial ischemia followed by infarction. In most cases, the right coronary artery supplies the inferior myocardium. Because of left dominance, the left circumflex will feed the posterior descending coronary artery in around 6-10% of the population.

The inferior wall is involved in about 40% of all inferior infarcts. Historically, inferior infarcts had a better prognosis than those in other areas of the heart, such as the front wall. An inferior wall inferior infarct has a mortality rate of less than 10%.

However, various aggravating conditions increase mortality, such as right ventricular infarction, hypotension, bradycardia, heart block, and cardiogenic shock.

Inferior Infarct Symptoms

Chest discomfort, heaviness or pressure, shortness of breath, and diaphoresis with radiation to the jaw or arms are all symptoms. Other symptoms such as tiredness, lightheadedness, or nausea are common.

Pay close attention to the heart rate during a physical exam since bradycardia and heart block might develop. Similarly, hypotension and indications of poor perfusion should be evaluated, mainly if a right ventricular infarction is present.

A high level of suspicion is necessary since there may be anomalous symptoms, particularly in women and elderly individuals. Because symptoms include nausea, vomiting, epigastric discomfort, and exhaustion, it is critical to examine the cardiac origins of these symptoms rather than dismissing them as gastrointestinal sickness.

EMS Cardiology || Tachy Tuesday: Inferior Myocardial Infarction (STEMI)

Inferior Myocardial Infarction Causes

Myocardial infarction (MI) is often caused by an imbalance in oxygen supply and demand, most commonly triggered by plaque rupture with thrombus development in an epicardial coronary artery, resulting in an abrupt decrease in blood flow to a section of the myocardium.

Inferior wall myocardial infarctions are caused by ischemia and infarction to the inferior part of the heart. The right coronary artery feeds the posterior descending artery in 80 percent of individuals (PDA) and provides the inferior wall of the heart through the posterior descending artery. In the other 20% of cases, the PDA is a branch of the circumflex artery.

There were 8.6 million myocardial infarctions globally in 2013. MIs in the inferior wall account for 40% to 50% of all MIs. They have a better prognosis than typical myocardial infarctions, with a death rate ranging from 2% to 9%. However, up to 40% of inferior wall MIs have concomitant right ventricular involvement, predicting a poor prognosis.

MI is caused by the rupture of a coronary artery plaque, thrombosis, and blocking downstream perfusion, resulting in myocardial ischemia and necrosis. In most cases, the culprit vascular is the right coronary artery, which supplies the posterior descending artery.

This anatomy is considered to be right dominant. Some people have left dominant architecture, with the posterior coronary artery fed by the circumflex artery. The most frequent ECG finding with inferior wall MI is ST elevation in ECG leads II, III, and a VF, with reciprocal ST depression in lead aVL. Because the right coronary artery supplies the AV node, inferior wall MIs are linked with bradycardias, heart blockages, and arrhythmias.

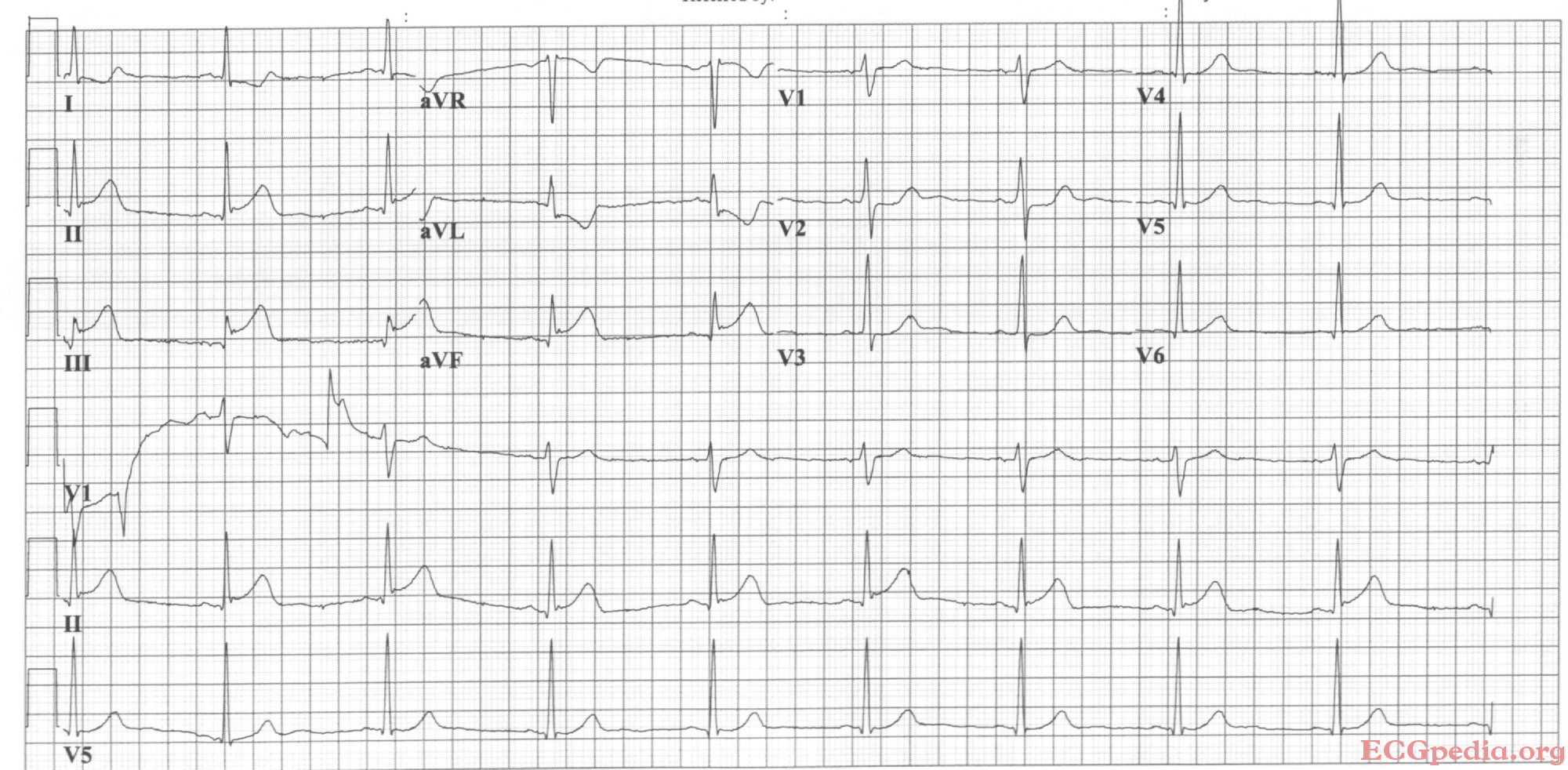

Inferior Infarct On ECG

The ECG remains the most useful diagnostic test in examining patients with suspected ischemia symptoms. Evidence of right bundle branch block (RBBB) in the event of acute MI also portends a similar bad prognosis, 80.

It may encourage consideration of immediate catheterization in persistent ischemia conditions and RBBB. Patients with chest discomfort and ECG abnormalities suggestive of STEMI should be evaluated for rapid reperfusion.

Analysis of the ECG lead constellation indicating ST elevation may also be beneficial in determining the location of the blockage in the infarct artery.

The magnitude of ST deviation on the ECG, the area of the infarction, and the length of the QRS all correlate with the probability of unfavorable outcomes. The degree of ST-segment resolution, in addition to the diagnostic and prognostic information provided in the 12-lead ECG, offers crucial noninvasive details on the effectiveness of STEMI reperfusion, regardless of whether it was accomplished with fibrinolysis or direct coronary intervention.

Although there is widespread agreement on electrocardiographic and vector cardiographic criteria for recognizing anterior and inferior myocardial wall infarctions, there is less agreement on criteria for lateral and posterior infarcts. Given the segmental structure of the heart as it lies in the thorax, the description "lateral" may be more suitable than "posterior."

However, the most current universal definition of MI preserves the distinction of posterior MI. Patients with an abnormal R wave in V1 (0.04-second duration and R/S ratio in the absence of preexcitation or RV hypertrophy) and inferior or lateral Q waveshave a higher risk of isolated occlusion of a dominant left circumflex coronary artery without collateral circulation; such patients have a lower EF, increased end-systolic volume, and a higher complication rate than those with inferior infarction due to isolated occlusion of the right coronary ST-segment increases in a VR, reflecting the basal intraventricular septum, may be seen in up to 30% of STEMIs and identify individuals at risk of left main coronary artery or multivessel disease, as well as poor prognosis.

Most STEMI patients develop serial changes on the ECG. Still, many factors limit the ECG's usefulness in diagnosing and localizing MI: the extent of myocardial injury, the age of the infarct, its location, the presence of conduction defects, previous infarcts, or acute pericarditis, and changes in electrolyte concentrations.

ST-segment and T wave abnormalities can be quite nonspecific and can occur in a variety of conditions, including stable and unstable angina pectoris, ventricular hypertrophy, acute and chronic pericarditis, myocarditis, early repolarization, electrolyte imbalance, shock, and metabolic disorders, as well as after digitalis administration.

Serial ECGs can separate these diseases from STEMI, but contemporaneous imaging may assist in identifying possible STEMI from alternative etiologies for early triage choices.

Many individuals will have the stigma of a STEMI on their ECG for the rest of their lives, especially if the Q waves develop; however, in a significant percentage of cases, the usual alterations fade, the Q waves regress, and ECG results may even recover to normal.

Inferior Infarct Treatment

Heart blocks are present in around 9% of patients, and two-thirds of patients who acquire a high-degree heart block during the acute course of an inferior wall MI do so within the first 24 hours. While heart blocks constitute a significant cause of morbidity and death, most high-degree heart blocks are curable with atropine. A temporary pacemaker is seldom required.

The injured myocardium may cause potentially fatal arrhythmias such as ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation. During the acute phase of the incident, these individuals must be observed in a monitored facility, often an intensive care unit. When potentially deadly arrhythmias develop, prompt defibrillation is critical.

If the ECG shows ST elevation, the patient should be transferred to the catheterization lab for emergency cardiac angiography, with a target door-to-vessel open time of less than 90 minutes.

Thrombolysis should be explored based on the facility's competence or the predicted lengthy travel time to an interventional catheterization lab. If there is evidence of a right ventricular infarction, avoid nitrates and increase volume to provide appropriate preload. The right ventricle has less myocardium than the left and relies on enough preload to ensure proper cardiac function.

If the right ventricle is damaged, preload decrease from nitrates might result in substantial hypotension. If this happens, resuscitation with intravenous crystalloids and maybe vasopressors is required. Other treatments include an aspirin dose of 162 to 325 mg, unfractionated heparin, a GP IIb/IIIa antagonist, and extra P2Y12 antiplatelet agents such as clopidogrel.

Managing a deficient wall MI necessitates the collaboration of a multidisciplinary team of nurses, doctors, heart surgeons, and cardiologists. Because these individuals are prone to life-threatening consequences, prevention is the recommended treatment. The nurse should inform the patients about the possibility of future pacing needs after they are discharged.

A low-salt and low-fat diet should be suggested by the nutritionist. The patient should be enrolled in a cardiac rehabilitation program. The pharmacist should urge smoking cessation, medication adherence, and blood cholesterol and glucose reduction.

Myocardial Infarction and Coronary Angioplasty Treatment, Animation.

Is Inferior Myocardial Infarction A Heart Attack?

An inferior myocardial infarction (MI) is a heart attack or a halt of blood flow to the heart muscle that affects the heart's inferior side. In 85% of patients, inferior MI is caused by a complete blockage of either the right coronary artery or the left circumflex artery. ST-elevation on the electrocardiogram (EKG) in leads II, III, and a VF characterizes inferior MI.

People Also Ask

What Leads To Inferior Infarct?

ECG with 12 leads reveal signs of inferior myocardial infarction (MI). Leads II, III, and a VF show ST-elevation. Leads I, aVL, V2, and V3 exhibit reciprocal alterations. Leads V5 and V6 also have some ST-elevation.

Is An Infarct A Heart Attack?

A shortage of blood flow may cause injury or destruction to the heart muscle. Myocardial infarction is another term for a heart attack. A heart attack requires immediate treatment to avoid death.

How Is Inferior Infarct Treated?

Fluid infusion is the primary mode of therapyfor RVI patients. Nitroglycerin and morphine may rapidly reduce blood pressure in the event of an inferior MI with right ventricular involvement.

Is Inferior Infarct Serious?

Inferior myocardial infarctions may have a variety of consequences and can cause death.

Conclusion

Occlusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery causes an anterior myocardial infarction. Electrical heart activity assessment utilizing 12-lead electrocardiography and cardiac biomarker analysis are critical diagnostic approaches in patients.

Patients with an inferior infarction exacerbated by a heart block, simultaneous precordial ST-segment depression, and RV involvement have bigger infarctions and a poorer prognosis than patients who do not have these symptoms.

Suleman Shah

Author

Suleman Shah is a researcher and freelance writer. As a researcher, he has worked with MNS University of Agriculture, Multan (Pakistan) and Texas A & M University (USA). He regularly writes science articles and blogs for science news website immersse.com and open access publishers OA Publishing London and Scientific Times. He loves to keep himself updated on scientific developments and convert these developments into everyday language to update the readers about the developments in the scientific era. His primary research focus is Plant sciences, and he contributed to this field by publishing his research in scientific journals and presenting his work at many Conferences.

Shah graduated from the University of Agriculture Faisalabad (Pakistan) and started his professional carrier with Jaffer Agro Services and later with the Agriculture Department of the Government of Pakistan. His research interest compelled and attracted him to proceed with his carrier in Plant sciences research. So, he started his Ph.D. in Soil Science at MNS University of Agriculture Multan (Pakistan). Later, he started working as a visiting scholar with Texas A&M University (USA).

Shah’s experience with big Open Excess publishers like Springers, Frontiers, MDPI, etc., testified to his belief in Open Access as a barrier-removing mechanism between researchers and the readers of their research. Shah believes that Open Access is revolutionizing the publication process and benefitting research in all fields.

Han Ju

Reviewer

Hello! I'm Han Ju, the heart behind World Wide Journals. My life is a unique tapestry woven from the threads of news, spirituality, and science, enriched by melodies from my guitar. Raised amidst tales of the ancient and the arcane, I developed a keen eye for the stories that truly matter. Through my work, I seek to bridge the seen with the unseen, marrying the rigor of science with the depth of spirituality.

Each article at World Wide Journals is a piece of this ongoing quest, blending analysis with personal reflection. Whether exploring quantum frontiers or strumming chords under the stars, my aim is to inspire and provoke thought, inviting you into a world where every discovery is a note in the grand symphony of existence.

Welcome aboard this journey of insight and exploration, where curiosity leads and music guides.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles