Liposome - Effects Of Liposome Assisted Drug Delivery

Liposomes are the most common and well-studied drug delivery nanocarrier. They stabilize therapeutic compounds, overcome obstacles to cellular and tissue uptake, and improve biodistribution of compounds to target sites in vivo. Liposomes are phospholipid vesicles with concentric lipid bilayers enclosing aqueous spaces.

Author:Suleman ShahReviewer:Han JuJul 18, 202360.6K Shares1.5M Views

Liposomesare the most common and well-studied drug delivery nanocarrier.

They stabilize therapeutic compounds, overcome obstacles to cellular and tissue uptake, and improve biodistribution of compounds to target sites in vivo.

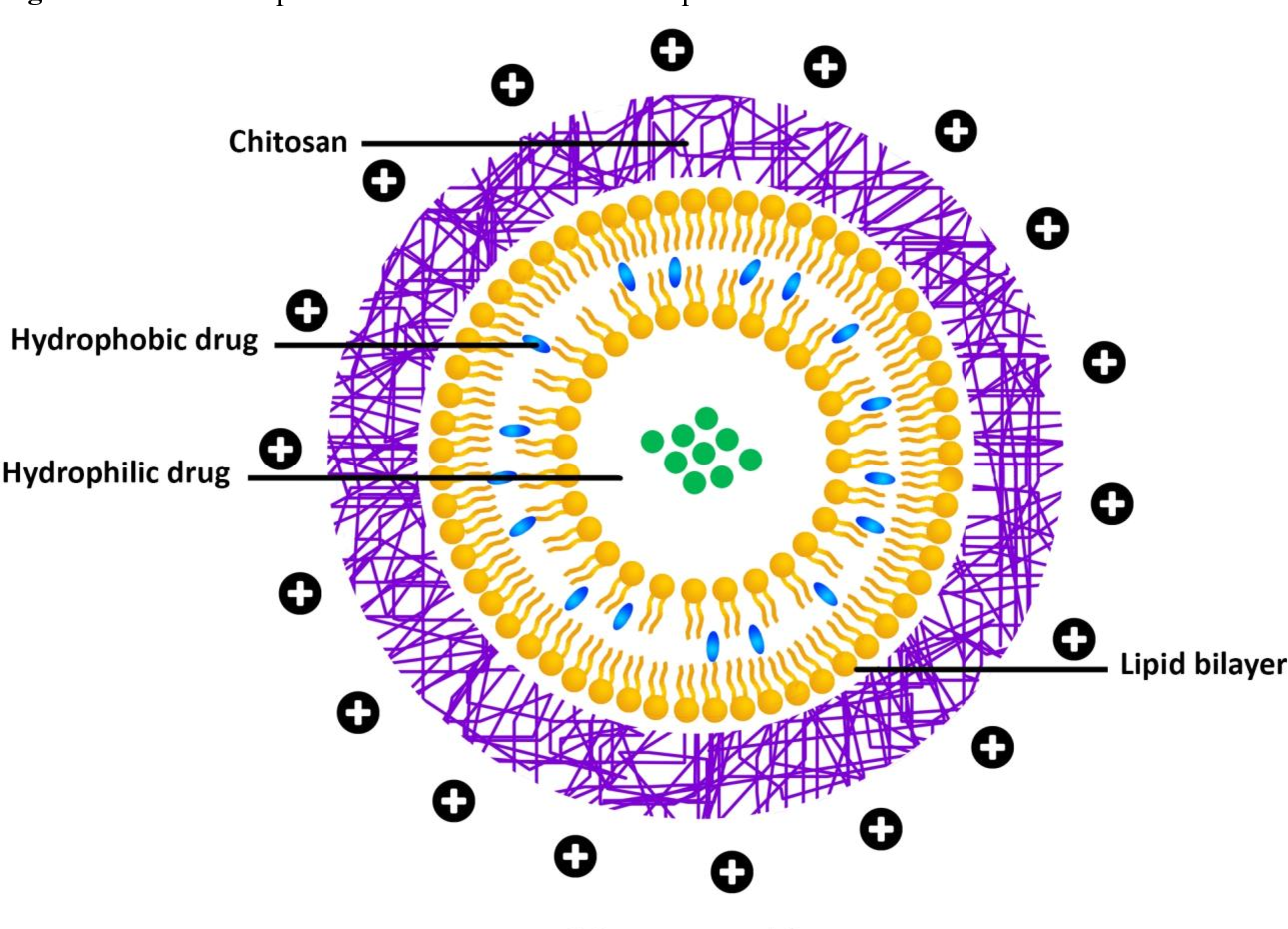

Liposomes are phospholipid vesicles with concentric lipid bilayers enclosing aqueous spaces.

Liposomal systems can encapsulate both lipophilic and hydrophilic compounds, allowing for a wide range of drugs. Hydrophobic molecules enter the bilayer membrane and hydrophilic molecules enter the aqueous center.

Large aqueous center and biocompatible lipid exterior deliver DNA, proteins, and imaging agents.

As a drug delivery system, liposomes offer biocompatibility, self-assembly, large drug payloads, and physicochemical and biophysical properties that can be modified to control their biological characteristics.

Types Of Liposomal Drug Delivery Platforms

There are four types of liposomal delivery systems: conventional, sterically-stabilized, ligand-targeted, and combinations. The first liposomes were conventional. A lipid bilayer made of cationic, anionic, neutral (phospho)lipids and cholesterol encloses an aqueous volume.

Liposomal delivery improved the therapeutic index of encapsulated drugs like doxorubicin and amphotericin in 1980s research. Conventional liposomal formulations reduce in vivo toxicity by modifying pharmacokinetics and biodistribution to improve drug delivery to diseased tissue. However, the delivery system was prone to rapid bloodstream elimination, limiting its therapeutic efficacy. Rapid clearance was due to opsonization of plasma components and uptake by fixed macrophages in the liver and spleen.

To improve liposome stability and blood circulation, sterically-stabilized liposomes were introduced. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is a hydrophilic polymer that stabilizes liposomes sterically.

Liposome Basics-Part one

Biological Challenges Facing Liposomal Drug Delivery Systems

As with any foreign particle, liposomes face multiple defense systems designed to recognize, neutralize, and eliminate invaders. They include RES, opsonization, and immunogenicity. While these obstacles must be overcome for optimal liposome function, other factors such as the EPR effect can enhance drug delivery.

The Reticuloendothelial System (RES) And Liposome Clearance

The RES accumulates systemically administered liposomes. RES organs include the liver, spleen, kidney, lungs, bone marrow, and lymph nodes. The liver has the highest liposomal uptake capacity, followed by the spleen, which can accumulate liposomes 10-fold higher. Fenestrations in RES microvasculature allow them to sequester liposomes from circulation. Pore diameters in these capillaries range from 100 to 800 nm, allowing extravasation and removal of most drug-loaded liposomes (50–1000 nm).

To remove liposomes, resident macrophages in the RES work directly with phagocytic cells. The RES takes up liposomes after vesicle opsonization, the adsorption of plasma proteins to the phospholipid membrane. Macrophages can clear liposomes without plasma proteins, according to in vitro studies.

Opsonins And Vesicle Destabilization

Interactions between liposomal drug delivery systems and plasma proteins affect nanocarrier biodistribution, efficacy, and toxicity. Plasma proteins play a key role in RES liposomal clearance via opsonization and vesicular destabilization. Liposome ozonation by serum proteins depends on size, charge, and stability. Small liposomes cannot support opsonic activity, so the interaction weakens from 800 to 200 nm. Liposome size affects complement recognition and liver uptake.

Large unmodified liposomes are eliminated faster than small, neutral, or positively charged ones. High electrostatic charge can still promote liposome interaction with opsonins. Large, charged liposomes are cleared by the liver and spleen within minutes and hours, respectively. Adding cholesterol increases liposome stability and reduces phospholipid exchange.

The Enhanced Permeability And Retention (EPR) Effect

Liposomes that have avoided both RES and opsonization undergo EPR. The EPR effect increases vascular permeability that supplies pathological tissues (such as tumors and inflammation). At these sites, deregulated angiogenesis and/or increased expression and activation of vascular permeability factors cause 300 to 4700 nm fenestrations. Liposomes can extravasate and accumulate by passive targeting. Inflammation alters blood vessel permeability by remodeling capillary vasculature to allow leukocyte diapedesis into peripheral tissue.

In vivo, tight junctional regions between endothelial cells are 12 to 20 nm wide, but inflammatory mediators increase microvascular permeability, forming 1 μm gaps. Size and number of pores vary depending on the pathological site's microenvironment. All liposomal delivery systems are subject to the EPR effect, with PEGylated liposomes having reduced RES clearance and extended circulation time.

Liposome Basics-Part two

The Accelerated Blood Clearance (ABC) Phenomenon

Interactions between liposome components and the immune systemhinder clinical translation. Synthetic modifications to improve their drug delivery can lead to antibody production against their components and/or cargo. Repeated injections of PEGylated liposomes lead to loss of their long-circulating properties and blood clearance. The "accelerated blood clearance" (ABC) phenomenon is the term used to describe this phenomenon.

The ABC phenomenon is a concern for PEGylated formulations that require multiple doses. Dams et al. observed the ABC phenomenon by showing that prior dosing of empty PEGylated liposomes influences the pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of the second dose in rats and rhesus monkeys. The second dose of PEGylated liposomes circulated less and accumulated more in the liver and spleen. The maximum clearance of liposomes in rats is 4–7 days after the initial dose, and in mice it's 10 days.

Complement Activation–Related Pseudoallergy (CARPA)

Some liposomal systems can trigger the innate immune response, leading to complement activation–related pseudoallergy (CARPA). The complement system is involved in immunological and inflammatory processes as part of the innate immune response. Liposomal drug therapycauses infusion-related hypersensitivity reactions in 2–45% of patients. Also, CARPA has been reported with experimental and clinically approved liposomal formulations (e.g., Doxil®, Ambisome, and DaunoXome®). CARPA causes anaphylaxis, facial flushing, facial swelling, headache, chills, and cardiopulmonary distress. General clinical management includes slowing the infusion rate or stopping therapy and using allergy medications (e.g., antihistamines, epinephrine, and corticosteroids).

Experimental Use Of Liposomes For Biomedical Applications

Liposomes offer promising new treatments for a wide range of pathologies. Since liposomes were discovered over 50 years ago, in vitro and in vivo lipid-based drug delivery research has increased. Liposomes are used to deliver drug molecules, gene therapy, and bioactive agents. Changes in lipid composition, charge, surface coatings, and ligands are investigated to improve efficacy, reduce RES clearance, and minimize toxicity. Active targeting, charged lipids, triggered release, and multi-functional formulations are used to improve conventional or stealth liposomal systems.

Active targeting approaches with conjugated targeting ligands on liposomes have been extensively studied for biomedical applications, especially after parenteral administration (e.g., intravenous and intraperitoneal injection). Targeting ligands are used to deliver encapsulated cargo to diseased tissues and cells with minimal non-target deposition. Conflicting results in the literature suggest ligand-targeted liposomes have a therapeutic advantage over non-targeted liposomes. In vivo studies have shown enhanced uptake and efficacy of ligand-targeted liposomes in diseased tissue.

Clinically Approved Liposomal-Based Therapeutics

Many liposomal products are on the market with more in development. Some of the most successful delivery methods use PEG-conjugated lipids. First FDA-approved nano-drug doxorubicin is delivered by PEGylated liposomes. PLD treats AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma, leukemia, and ovarian, breast, bone, lung, and brain cancers. PLD is an effective alternative to doxorubicin in cardiac dysfunction patients.

When doxorubicin is encapsulated in PEGylated liposomes, it reduces RES uptake and prolongs serum and plasma half-life. This helps PLD accumulate in tumor tissue rather than healthy tissues. PLD ensures that doxorubicin passes through the myocardium without causing cell toxicity. Finally, PLD avoids high plasma peak levels of free drug, which is linked to cardiotoxicity.

In addition to PLD's 1995 FDA approval, combination therapies (such as bortezomib for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma) have recently been approved. Another PEGylated liposome in Phase I trials is PEPO2, an irinotecan-encapsulated liposomal formulation used to treat advanced refractory solid tumors. PEGylated stealth liposomes of camptothecin are in Phase I trials for ovarian cancer.

Why Is The Translation Into Clinical Practice Slow?

Despite 50 years of research, clinical translation of liposome-assisted drug delivery platforms has not progressed as quickly as positive results suggested. Liposomal formulations have shown therapeutic advantages for many biomedical applications, but the bottleneck is due to pharmaceutical manufacturing, government regulations, and intellectual property (IP). Similar challenges face other nano-delivery systems in the clinic. Pharmaceutical development is limited by cost and quality. Nano-delivery systems are affected by (i) scalability of the manufacturing process, (ii) reliability and reproducibility of the final product, (iii) lack of equipment and/or in-house expertise, (iv) chemical instability or denaturation of the encapsulated compound in the manufacturing process, and (v) long-term stability issues.

Suitable methods for industrial-scale production of conventional liposomes have been developed without using organic solvents. The challenges arise when the liposomal delivery system becomes more complex, such as by adding coatings and/or ligands.

People Also Ask

What Are The Disadvantages Of Liposomes?

The cost of production is quite high. Drugs or molecules that have been encapsulated can escape and combine with one another. Phospholipid can sometimes be seen to go through processes that are analogous to hydrolysis and oxidation. Short duration of half-life

How Does Liposome Help In Drug Delivery?

Liposomes shield certain drugs from the effects of enzymes while also preventing them from being degraded chemically and immunologically. Liposomes also protect these drugs from the effects of chemical and immunological breakdown. Because of the sustained levels of drug that liposomes provide, the toxicity of the medication can be reduced, and the necessary dosage can be decreased as a result.

What Is A Liposomal Delivery System?

Liposomes are vehicles for effective delivery of substances into the body. They do this by either facilitating absorption directly in the mouth or preventing breakdown by stomach acid.

Why Are Liposomes Unstable?

In general, the highly unsaturated phospholipid compounds can cause the liposome structure to become unstable. Since lipids derived from biological sources like eggs and soybeans frequently contain high concentrations of unsaturated fatty acids, they are by definition less stable than their synthetic counterparts.

Conclusion

The use of liposomes to aid drug delivery has impacted many biomedical areas. Understanding the advances in liposomal technologyand the remaining challenges will allow future research to improve existing platforms and overcome translational and regulatory barriers. Continued translational success will require communication and collaboration between experts in all stages of liposomal technology development, including manufacturing, design, cellular interactions, toxicology, and preclinical and clinical evaluation.

Suleman Shah

Author

Suleman Shah is a researcher and freelance writer. As a researcher, he has worked with MNS University of Agriculture, Multan (Pakistan) and Texas A & M University (USA). He regularly writes science articles and blogs for science news website immersse.com and open access publishers OA Publishing London and Scientific Times. He loves to keep himself updated on scientific developments and convert these developments into everyday language to update the readers about the developments in the scientific era. His primary research focus is Plant sciences, and he contributed to this field by publishing his research in scientific journals and presenting his work at many Conferences.

Shah graduated from the University of Agriculture Faisalabad (Pakistan) and started his professional carrier with Jaffer Agro Services and later with the Agriculture Department of the Government of Pakistan. His research interest compelled and attracted him to proceed with his carrier in Plant sciences research. So, he started his Ph.D. in Soil Science at MNS University of Agriculture Multan (Pakistan). Later, he started working as a visiting scholar with Texas A&M University (USA).

Shah’s experience with big Open Excess publishers like Springers, Frontiers, MDPI, etc., testified to his belief in Open Access as a barrier-removing mechanism between researchers and the readers of their research. Shah believes that Open Access is revolutionizing the publication process and benefitting research in all fields.

Han Ju

Reviewer

Hello! I'm Han Ju, the heart behind World Wide Journals. My life is a unique tapestry woven from the threads of news, spirituality, and science, enriched by melodies from my guitar. Raised amidst tales of the ancient and the arcane, I developed a keen eye for the stories that truly matter. Through my work, I seek to bridge the seen with the unseen, marrying the rigor of science with the depth of spirituality.

Each article at World Wide Journals is a piece of this ongoing quest, blending analysis with personal reflection. Whether exploring quantum frontiers or strumming chords under the stars, my aim is to inspire and provoke thought, inviting you into a world where every discovery is a note in the grand symphony of existence.

Welcome aboard this journey of insight and exploration, where curiosity leads and music guides.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles