Suprascapular Neuropathy Related To Rotator Cuff Tears - A Short Review

Are you familiar with suprascapular neuropathy related to rotator cuff tears? It has become a topic of discussion but there are only few studies to support it in cases of massive RCTs.

Author:Suleman ShahReviewer:Han JuJan 19, 202448K Shares787.1K Views

A study by A. Thomas published in 1936 by the journal La Presse Médicalefirst described suprascapular nerve (SSN) entrapment neuropathy occurring at the transverse scapular notch.

Although isolated SSN neuropathy is a relatively rare phenomenon, its etiology is thought to be related to traction or compression of the SSN.

Commonly referred to as a “sling effect,” this mechanism is well reported in the literature.

Patients with SSN entrapment often present with pain, weakness, and numbness of the shoulder and a historyof symptoms provoked by dominant upper extremity movement.

The condition may also be associated with atrophy of the supraspinatus or infraspinatus muscle. Therefore, this manifestationclosely resembles that of rotator cuff tears.

Recently, suprascapular neuropathy related to rotator cuff tears has become a subject of conversation.

Rotator cuff tears medialize muscle fibers and tether the SSN at the suprascapular notch; thus, resulting in suprascapular neuropathy.

When advancement of the rotator cuff or interval slides (anterior or posterior) is indicated in cases of massive cuff tears, the SSN needs to be retracted further; thus, increasing the risk of damage.

SSN Anatomy

The SSN is a mixed peripheral nerve that contains motor and sensory fibers and originates at the ventral rami of the spinal nerves C-4, C-5 and C-6 or at the upper trunk of the brachial plexus.

The SSN provides motor innervation to the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles.

In addition, it branches to the coracohumeral and coracoacromial ligaments, subacromial bursa and acromioclavicular joint.

After approaching the shoulder joint, the nerve passes through the suprascapular notch before supplying motor branches to the supraspinatus muscle and sensory branches to the acromioclavicular and glenohumeral joints.

The nerve continues past the spinoglenoid notch and supplies motor branches to the infraspinatus muscle.

Historically, the SSN has been thought to have no cutaneous branches; however, in his study published in 1980 by the Journal of Anatomy, Masaharu Horiguchi described the existence of sensory cutaneous branches in 1968.

In a report published in 1994 by the Journal of Anatomy, M.L. Ajmani, cutaneous branches of the SSN were observed in 14.7% of the cases.

On the other hand, in a study published in 2008 by the Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, its authors, with Willie Vorster as lead author, observed in 87.1% of the cases.

In addition, in their case report published in 2000 by the journal Neurosurgery, Dr. Kimberly S. Harbaugh, Dr. Rand D. C. Swenson, and Dr. Richard L. Saunders reported a single case of SSN entrapment characterized by an area of numbness involving the upper lateral shoulder region.

Anatomic studies have shown that the morphology of the suprascapular notch is highly variable in termsof width and shape.

In a case report published in 1979 by the journal Neurosurgery, its authors, with S. S. Rengachary as lead author, examined adult cadaveric scapulae and categorized the suprascapular notch shape into six types.

Rengachary’s categorization of notch shape is regarded as a de facto standard.

A U-shaped notch (Type 3) was the most common type and was identified in 48% of the cadavers examined.

The morphology of the transverse scapular ligament (TSL), including width, thickness, and rate of ossification, was also highly variable. The TSL is a unique ligament that connects to different parts of the scapula.

The biomechanical role of the ligament is unclear; however, in a study published in 2001 by the Journal of Anatomy, the authors, with Dr. Bernhard Moriggl as lead author, described the fibrocartilage at the enthesis of the TSL, suggesting that the ligament responds to both compressive and tensile loading.

There is a complementary relationship between the width of the suprascapular notch and the thickness of the TSL.

Anterior to the TSL, an accessory ligament named as the anterior coracocapsular ligament is present in 60% of the specimens.

Although its impact on SSN entrapment neuropathy remains unclear, the anterior coracocapsular ligament substantially narrows the suprascapular foramen.

A narrow notch shape together with a thick TSL has been hypothesized to be associated with nerve entrapment; however, no direct correlation has been demonstrated.

Rotator Cuff Tears And SSN Neuropathy

Several clinical and anatomical studies suggest a relationship between rotator cuff tears and SSN neuropathy.

Moreover, measures to relieve pain after failed cuff repair have been explained in the context of SSN decompression.

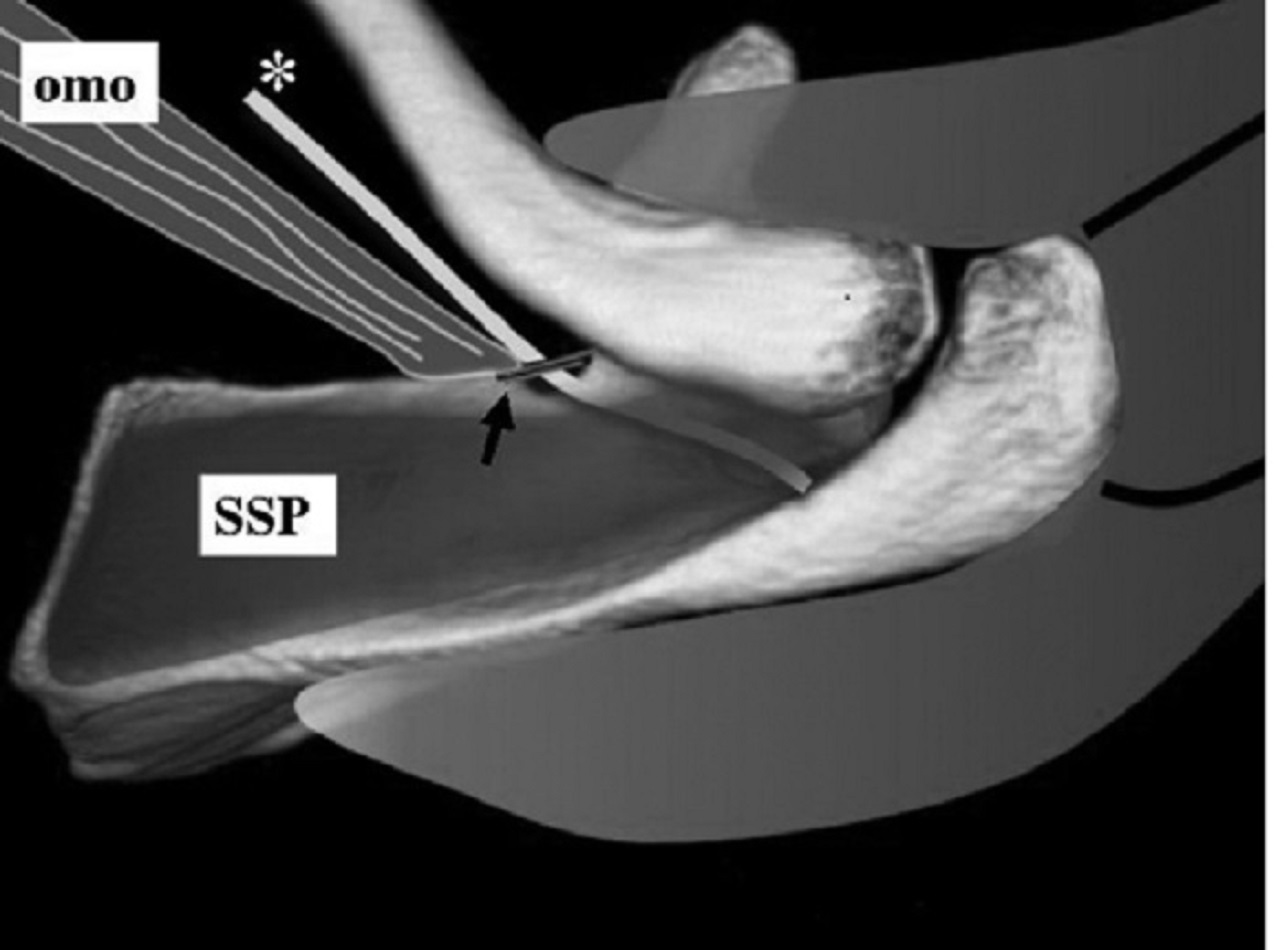

Retracted rotator cuff tears medialise muscle fibers and tether the SSN, which is relatively fixed at the point where it passes through the suprascapular notch.

More extensive retraction (such as that in the case of massive rotator cuff tears) causes increased nerve traction.

During retraction, the nerve is vulnerable to compression. This is more of a concern when advancement of the rotator cuff or interval slides (anterior or posterior) is indicated.

Several authors have confirmed that lateral advancement of the supraspinatus muscle causes compression of the nerve and should be limited to 1 centimeter, otherwise the branches of the SSN may be damaged.

In a study published in 1992 by the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, its authors, with J. P. Warner as lead author, examined 31 cadaver shoulders. They found that the SSN was relatively fixed on the floor of the fossa underneath the TSL.

The motor branches to the supraspinatus muscle were significantly shorter than those to the infraspinatus muscle.

In 84% of the shoulders examined, the first motor branch originated underneath the TSL or just distal to it.

In one shoulder (3%), the first motor branch passed over the ligament.

The standard anterosuperior approach allowed only 1 centimeter of lateral advancement of either tendon.

In a study published in 2003 by the Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, the authors, with Dr. Andreas Greiner as lead author, evaluated 24 cadaver shoulders to assess SSN damage during advancement of the supraspinatus muscle for rotator cuff repair.

They identified four different patterns of branching and courses of the SSN:

- branches located medial to the scapular notch (95.8%)

- branches running in a posterior direction and crossing the bottom of the muscle on an extramuscular course (54.2%)

- branches running in a posterior direction on an intramuscular course (12.5%)

- branches located lateral to the scapular notch, whereby they either remained inside the supraspinatus fossa (25%) or ran toward the infraspinatus fossa (16.6%)

They found that the entire neurovascular pedicle was tethered after advancement; however, the subgroup with the branches located medial to the notch was at a greater risk of tethering and tension during advancement of the muscle 1 centimeter laterally.

In a study published in 2003 by the Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, the authors, with Dr. Vijay B. Vad as lead author, retrospectively defined the prevalence of peripheral nerve injury associated with full-thickness rotator cuff tears presenting with shoulder muscle atrophy.

The prevalence of associated suprascapular neuropathy was observed in 8% (2/25) of the patients examined by electrodiagnostic testing, including nerve conduction studies and needle examination.

In their study published in 2006 by the Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, Dr. William J. Mallon, Dr. Robert J. Wilson, and Dr. Carl J. Basamania reported two of four patients with massive retracted rotator cuff tears and suprascapular neuropathy who demonstrated reinnervation potentials after partial arthroscopic rotator cuff repair.

In a study published in 2007 by the journal Arthroscopy, the authors, with Dr. John G. Costouros as lead author, reported that all six patients with preoperative electrodiagnostically confirmed suprascapular neuropathy showed nerve recovery after partial or complete rotator cuff repair.

In their case report published in 2000 by the Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, Dr. Akihiko Asami, Dr. Motoki Sonohata, and Dr. Keizo Morisawa reported a case of bilateral SSN entrapment associated with rotator cuff tears.

In this case, decompression of the SSN by releasing the TSL brought diminished pain, weakness and atrophy of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles.

In their study published in 1984 by the journal Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, P. E. Kaplan and Dr. William T. Kernahan, Jr. also reported six cases of the rotator cuff tears concomitant with SSN neuropathy diagnosed by electromyography (EMG).

However, in a study published in 1997 by the Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, its authors, with Dr. Robert M. Zanotti as lead author, retrospectively reviewed the incidence of cuff repair and injury to the SSN after mobilization and repair of a massive rotator cuff tear.

After a mean follow-up period of 2.5 years, electromyographic examination confirmed that one of 10 patients had an iatrogenic SSN injury.

They concluded that operative injury to the SSN during rotator cuff mobilization can occur, but other factors such as inadequate cuff muscle function are more frequently responsible for the poor functional outcomes observed after successful repair of massive rotator cuff tears.

Other researchers proposed that severe fatty degeneration in patients with massive rotator cuff tears are caused by SSN damage.

In a study published in 2010 by the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, the authors, with Kasra Rowshan as lead author, examined a rabbit subscapularis tenotomized model and concluded that fatty infiltration of the muscle occurs with chronic rotator cuff tears and may be explained by nerve injury.

In a comparative study published in 2012 by the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, its authors, with Xuhui Liu as lead author, demonstrated that significant and consistent muscle atrophy and fatty infiltration were observed in the rotator cuff muscles after rotator cuff tendon transection.

They found that denervation significantly increases the amount of muscle atrophy and fatty infiltration after a rotator cuff tear.

However, using a rabbit model, In a study published in 2013 by the Journal of Orthopaedic Research, the authors, with J. Christopher Gayton as lead author, showed that rotator cuff tears do not affect the motor endplate or innervation status of the supraspinatus, suggesting that fatty degeneration occurs independent of denervation of the supraspinatus.

Diagnostic Studies

EMG of the SSN is thought to be a useful diagnostic tool in cases of primary SSN neuropathy.

However, the sensitivity and specificity of EMG and Nerve Conduction Velocity (NCV) varies from 74% to 91%, thus a negative result does not necessarily preclude SSN neuropathy.

Furthermore, because SSN entrapment related to rotator cuff tears is thought to be a dynamic phenomenon, the co-existence of SSN neuropathy and rotator cuff tears may not always be demonstrable on EMG.

Magnetic resonance imaging is also helpful in identifying changes in the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles secondary to denervation, such as:

- decreased muscle bulk

- fatty infiltration

- homogeneous high-signal intensity on T2-weighted images

In their comparative study published in 2013 by the Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, Silvan Beeler, Eugene T. H. Ek, and Christian Gerber observed the appearance of fatty infiltration and muscle atrophy on magnetic resonance imaging when comparing cases of rotator cuff tears and suprascapular neuropathy.

They found that chronic rotator cuff tendon tears and suprascapular neuropathy were both associated with fatty infiltration and muscle atrophy; however, the pattern of fatty infiltration is markedly different in the two situations.

These findings may have diagnostic potential.

In a review published in 2011 by the Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, authors Laurent Lafosse, Kalman Piper, and Ulrich Lanz described the “SSN stretch test,” which was judged to be positive (related to SSN neuropathy) if it reproduced or exacerbated pain in the posterior aspect of the shoulder.

In this test, the clinician stands behind the patient and performs lateral rotation of the patient’s head away from the affected shoulder, holding it gently in position while using the other hand to gently retract the shoulder.

However, they did not present clinical data in this study, and the clinical value of this technique is still under evaluation.

Indication For SSN Decompression

Whether to release the SSN in cases of massive rotator cuff tears remains an unanswered question.

The open technique for decompression via a superior incision requires extended dissection and is technically difficult.

With advances in arthroscopic technique, studies have reported the advantages of all-arthroscopic decompression of the SSN over the open technique.

All, but one, of the currently performed arthroscopic decompression techniques are through the subacromial space, although in their study published in 2009 by the Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, John R. Reineck and Sumant G. Krishnan reported a technique for viewing and approaching from the anterior to the coracoid.

They used a portal created medially to the coracoid to explore and dissect the TSL.

All of these procedures could be performed continuously or antecedently with arthroscopic rotator cuff repair.

It is regarded as a difficult procedure and is associated with a steep learning curve, though Laurent Lafosse, Kalman Piper, and Ulrich Lanz described that release of the nerve is a safe and simple technique with little risk of additional complications.

Till date, there has been no compelling study showing a clear relationship between rotator cuff tears and SSN neuropathy, suggesting that there is no clear indication for SSN decompression concomitant with rotator cuff repair, even if technically possible.

Lafosse, Piper, and Lanz proposed the following indications for SSN release:

- patients presenting with weakness of the infraspinatus with or without wasting of the supraspinatus,

- with or without pain, and

- with or without positive EMG findings;

- patients with a thickened or ossified ligament on assessment during arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, and

- patients who present with posterior shoulder pain with a positive SSN stretch test

However, large numbers of massive cuff tear cases are with muscle atrophy and no direct correlation has been demonstrated between SSN neuropathy and morphology of the suprascapular notch or TSL.

Further research will be necessary to fully understand the role of decompression as well as the long-term outcomes of arthroscopic decompression.

Conclusion

Till date, there are a few studies to support SSN neuropathy in cases of (massive) rotator cuff tears.

There are also a few studies showing the indication for concomitant SSN release; however, several clinical and basic studies provide some evidence that SSN injury may be a part of the disease spectrum of rotator cuff pathology.

Future studies about suprascapular neuropathy related to rotator cuff tears will hopefully serve to elucidate these issues.

Suleman Shah

Author

Suleman Shah is a researcher and freelance writer. As a researcher, he has worked with MNS University of Agriculture, Multan (Pakistan) and Texas A & M University (USA). He regularly writes science articles and blogs for science news website immersse.com and open access publishers OA Publishing London and Scientific Times. He loves to keep himself updated on scientific developments and convert these developments into everyday language to update the readers about the developments in the scientific era. His primary research focus is Plant sciences, and he contributed to this field by publishing his research in scientific journals and presenting his work at many Conferences.

Shah graduated from the University of Agriculture Faisalabad (Pakistan) and started his professional carrier with Jaffer Agro Services and later with the Agriculture Department of the Government of Pakistan. His research interest compelled and attracted him to proceed with his carrier in Plant sciences research. So, he started his Ph.D. in Soil Science at MNS University of Agriculture Multan (Pakistan). Later, he started working as a visiting scholar with Texas A&M University (USA).

Shah’s experience with big Open Excess publishers like Springers, Frontiers, MDPI, etc., testified to his belief in Open Access as a barrier-removing mechanism between researchers and the readers of their research. Shah believes that Open Access is revolutionizing the publication process and benefitting research in all fields.

Han Ju

Reviewer

Hello! I'm Han Ju, the heart behind World Wide Journals. My life is a unique tapestry woven from the threads of news, spirituality, and science, enriched by melodies from my guitar. Raised amidst tales of the ancient and the arcane, I developed a keen eye for the stories that truly matter. Through my work, I seek to bridge the seen with the unseen, marrying the rigor of science with the depth of spirituality.

Each article at World Wide Journals is a piece of this ongoing quest, blending analysis with personal reflection. Whether exploring quantum frontiers or strumming chords under the stars, my aim is to inspire and provoke thought, inviting you into a world where every discovery is a note in the grand symphony of existence.

Welcome aboard this journey of insight and exploration, where curiosity leads and music guides.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles